THE PICK-POCKET

by Timeri N. Murari.

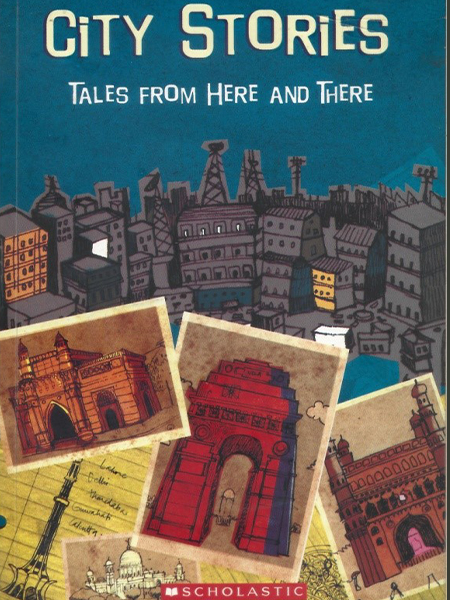

A collection of short stories published by Scholastic India

Kant, who named himself after the last syllable of his favourite movie star’s name as he did not possess a family name or an ancestral place, and who had escaped from his master, arrived early in the morning by the Pandian Express at Chennai Central Station. He had never been in Chennai before, but he had heard it was a city with many prospects for a boy like him who had honed his talents well.

He drifted along with the crowd towards the exit. It was always a good time to pick a pocket, his master, Selvam, a minor history-sheeter with many talents, had taught him. Selvam was also a minor magician and while he distracted his audience, Kant would wander among them, expertly relieving the men of their wallets. Selvam always took all the money and only gave Kant a cuff on his head for not extracting more. It was after one of these performances, that Kant decided to run away and try his luck elsewhere.

Although he was nearly fourteen years old, Kant could not read or write, as he had never been to school. But he was a better magician than Selvam. The previous evening, in Madurai station, he had earned the princely sum of five rupees through his magician’s talents. Watching him was an old couple, and Kant was aware that the man had remained intently watching the other tricks before moving on with his wife.

When he was in a crowd, it was his habit to watch young children with their parents, and he did this now, making his way towards the exit. He stared with longing, imagining he was that boy who held onto his mother’s hand or that boy walking beside his father. How he envied those children. He could have been one of them, walking with his mother and father, holding their hands, feeling the warmth of their love. He used to pray each night that he would find them, and them him. But as years passed and he had stopped those prayers.

He had work to do if he was to survive alone in this huge city. A few steps ahead walked the old couple. He had noticed them again as they’d cautiously clambered down from the IInd class a/c compartment. The man had tenderly helped his wife down, holding her hand and now wheeled their trolley case behind him. Kant had noted the sagging bulge in the left hand pocket of the man’s crumpled white kurta; his wife wore a cotton saree, also crumpled from sleeping in it.

Kant quickened his pace. The couple stopped suddenly; people collided with them. As Kant passed the old man, he dipped his hand swiftly into the kurta pocket and, with two supple fingers strong as pliers, easily removed the wallet. In almost the same easy motion, he slipped it under his ragged shirt and tucked into the waistband of his trousers.

As he started to quicken his step, the old man called out. ‘Thambi.’

Kant’s heart raced, and he was ready to run but the man’s voice had not been angry. He had to remain calm. He turned, trying a smile.

‘Here,’ the old man said, holding out an apple. ‘We would like you to have this.’

Kant took it in surprise. He never expected kindness from people.

The old woman smiled too. ‘We thought you looked hungry. ’ She turned to her husband. “He does look like Prakash, doesn’t he?’

‘Yes, very much like him.’

Kant hurried past them, and didn’t look back. He was tensed and ready to run should the old man have noticed the theft and called out. Strangely, instead of feeling gratitude Kant felt angry. People shouldn’t surprise him with acts of kindness; there should be a law against that. He wasn’t about to return the wallet just because they gave him an apple. There was a rubbish bin by a pillar and quite deliberately Kant dropped the apple into it, getting rid of any guilt that might have contaminated him.

He was eager to see what he had stolen. He saw a gap among the shops, slid into it and pulled out his prize. He opened the wallet slowly, peeked in, and sighed with pleasure. There were four one hundred rupee notes, and three ten rupee notes. Stuffed in a separate compartment was a single sheet of paper, about the size of the one hundred rupee note. He didn’t look at it. He stuffed the cash in his pocket and dropped the wallet through the railings into the railway compound behind the shops. There, he said to himself, that’s what I think of them and their apple.

First things first, he was starving. He had not eaten since the day before. Across the busy road were three or four eateries. He dodged the continuous traffic, and went into the first eatery and grandly ordered a thali.

‘Where’s your money?’ the man at the counter demanded. Kant took out a one hundred rupee note and waved it under his nose. Kant ate greedily, and walked out. Further down that footpath was a clothes shop and Kant who loved to look stylish and neat, bought a yellow shirt and blue jeans. He changed into them, leaving his ragged old clothes for the shop keeper to get rid of.

Quite naturally, when this initial exploration was over, he gravitated back towards Central station. It would not only be his base until he found another one, but also a source of money.

As he entered the station, he stopped suddenly. The old couple was sitting on a bench, looking very sad and beside them was the police constable. A constable had a note book in his hand and was writing down what they told him.

Kant started to turn away when he heard the woman call out to him. ‘Thambi, did you like our apple?’

Reluctantly, dragging his feet, avoiding the constable’s glance, he returned. ‘Yes,’ he lied. ‘What has happened?’

The old man sighed. ‘I have mislaid my wallet.’ He turned back to the constable. ‘It’s not the money; there were only a few hundred rupees. But there was a cheque in it and it’s our whole life’s savings. I sold my ancestral property in Madurai. The buyer gave the cheque for the property and went back to America. We have to pay for our new flat by tomorrow, our final home. Otherwise, we’ll be evicted.’

‘It is a nuisance,’ the old woman said, not with any anger. Nor did she show any anger towards her husband.

Kant, who survived without any guilty conscience, now wished he had not heard this tale. He quietly drifted away and found himself moving towards the wall of the compound, to where he’d dropped that wallet. He spotted it lying in the dirt. He walked over, looked around—no one was watching—and scooped it up swiftly. Reluctantly, he took the remaining three hundred and twenty rupees from his pocket, and slipped the notes back into the wallet. He hoped the old man wouldn’t object to him having some food and new clothes. He tucked the wallet into his waist band under his shirt and strolled back to the station.

The woman’s bag was by her feet. He would drop the wallet in it. Kant took out his change and dropped the coins so they rolled towards the bag. As he bent over to gather the coins, he brushed past the old man. Kant reached under his shirt. The wallet was gone. He straightened, bewildered. Had it fallen out? It had been there a moment before when he had bent down. As he turned to see if he had dropped it, the constable grabbed him by the neck.

‘Caught you, you thief.’

‘Thief,” Kant protested indignantly. ‘I’ve not stolen anything You can search me, if you want.’

The constable did, very roughly, and didn’t find the wallet. The old man rummaged in the bag and brought out an apple and held it out to Kant. As Kant took it, the old man delved back into the bag and pulled out the wallet. His face was level with Kant’s, and he winked into Kant’s puzzled eyes.

The old man held up the wallet, surprise on his face. He smiled apologetically. ‘The problem with old age is one forgets where one has placed things. I must have put it in my wife’s bag. I am so sorry to have caused you all such trouble.’

‘Please check—is there anything missing?’ the constable asked, still holding Kant.

Very slowly, the old man counted the money.

Kant wriggled. Now, he was in trouble; he was stupid to have returned. But he was curious. How did the wallet end up in the bag and why had the old man lied?

‘Nothing is missing,’ the old man said.

‘And the cheque?’ the constable asked.

‘It’s here too.’

Reluctantly the constable released Kant, and left.

‘Thank you for returning my wallet,’ the old man said

‘You knew I’d stolen it?’ Kant said.

‘Oh yes, you were the only one who could have. I knew you’d come back to the station after you’d spent some money. When I saw you go away and return again I knew you had my wallet and that you have a good heart.’

‘But how did it get in the bag?’

‘I picked it from your trouser band. I saw you performing in Madurai station,’ the old man said, and his wife nodded smiling. ‘You’re not a bad magician. I could teach you be a great magician and not live the life of a pick-pocket.’

‘He looks just like Prakash when he’s puzzled,’ the wife commented.

‘Teach me?’ Kant asked warily. ‘Who are you to teach me?’

‘I was one of the greatest magicians of all when I was young,’ the old man said with quiet pride. ‘I was known as Mandrake the Magician—it was a name I took from a comic book. I travelled all over the world, performing my magic.’

‘Who’s this Prakash you keep talking about?’ Kant asked.

The old woman said. ‘He’s a scientist and lives in America. We have not seen him for many years now. He hated magic.’

‘It’s only cheap illusion, he told me,’ the old man said. ‘But everything in life is illusion.’

They gathered their bags and moved towards the auto rickshaw stand. Kant remained watching them, wondering what he should do.

The old man turned. ‘Well, are you coming with us so I can teach you to be a great magician? Or will you stay here and be a bad pick-pocket?’

Warily, Kant said. ‘You’re not going to treat me like a servant?’

‘Of course not,’ the old woman said. ‘You look too much like Prakash, our son.’