SHE HAS MY NAME

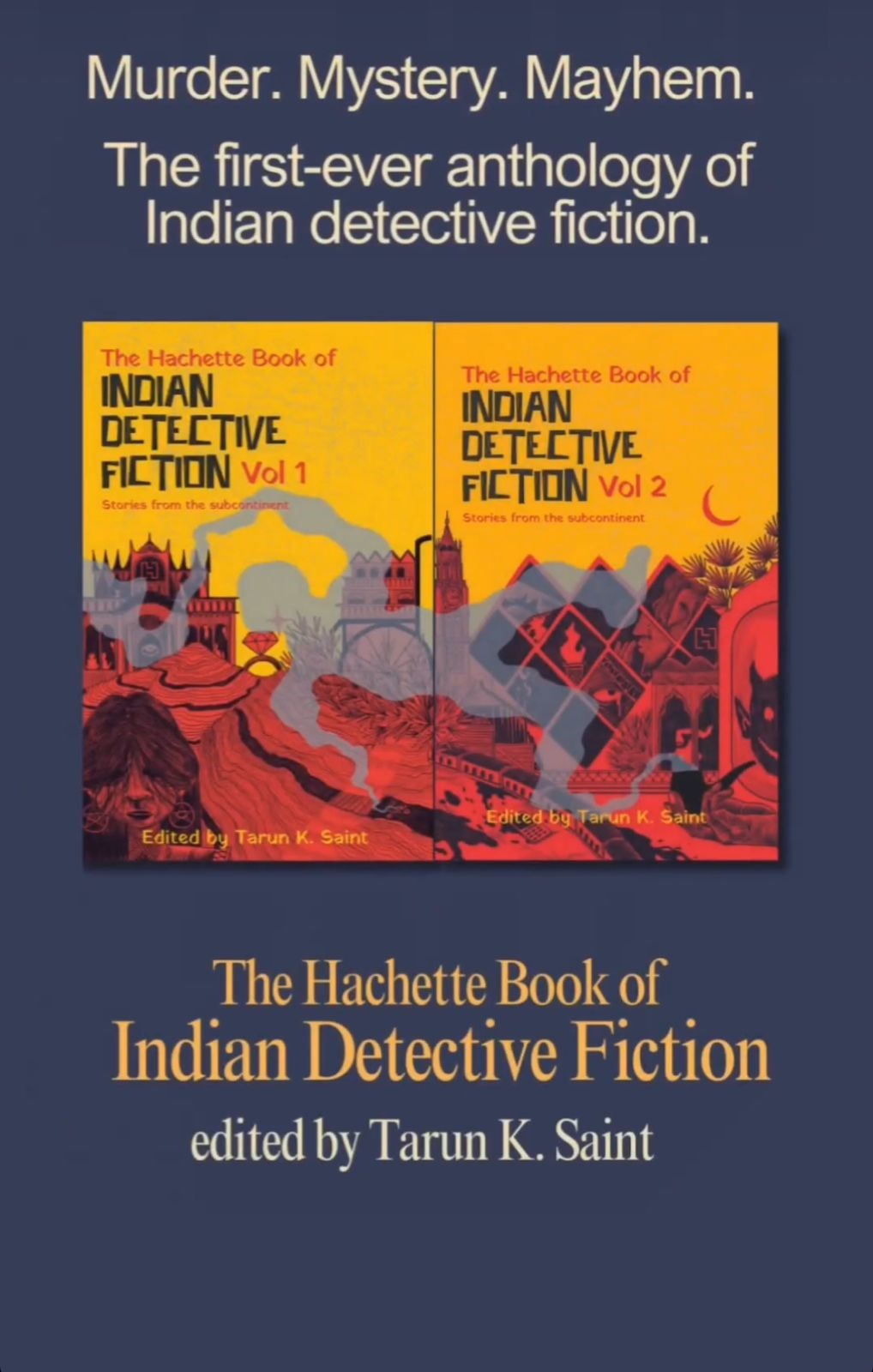

Publisher Hachette Book of Crime Short Stories.

She waited exactly where she had told him she would. Round the corner from the metro station, down the quiet, residential street with free parking. She was prepared to wait all day. She had her phone, a book, a thermos of coffee and samosas. He would come. Would she recognize him? He would have to change his appearance as his bearded features were recognizable in the newspapers and on television. But he would not be able to disguise those heavy-lidded, piercing eyes. It had been many years since she had seen him in the flesh.

He came into the country for the body of his daughter. He knew it was a trap, but he believed she should lie in the land of his birth and not in the enemy’s. She had been killed, so young and beautiful, to pay for his sins against the State. The State had alienated him on the murder of his father, a man of wisdom and steadfastness of purpose against the injustices of the State, when he was around the same age as his daughter. It had murdered his daughter to draw him out, knowing that he would not rest until he had recovered her body to lie beside the graves of his father, mother and grandparents. His brothers too lay in the same graveyard.

The men who helped him enter the country on his new passport, with a false name and in the photograph clean-shaven and so youthful, did not ask for money. They wanted only a favour, to kill a man for them and then they would take him and his daughter’s body safely back to his homeland. They were from his country, exiles who claimed to support the cause and were overly deferential to him. You are our hero, they said in unison and bowed in unison, expecting him to be swayed by such flattery. They gave him the photograph of the man he would kill, a gun and left him outside the building, telling him they would wait for him in the car. When he returned to the street, the car had gone. This betrayal didn’t surprise him. He expected that, always.

He didn’t drop the weapon but tucked into his waistband and walked unhurriedly up the street towards the metro station. It was winter and he wore a light leather jacket, pressed jeans and an open neck shirt. He didn’t look out of place but a good citizen. It was mid-afternoon and the street deserted. The town and the streets were familiar. The homes were behind high walls, the gates protected by sleepy guards in crumpled uniforms.

He passed a parked car in which a man and a woman were arguing fiercely with the windows closed. He didn’t pause when the man slapped her hard and only hesitated when he heard the shot, a muffled crack. He glanced back as the woman climbed out of the car. Inside, the man slumped against the window.

She asked him if he would help her. He said nothing but returned to the car and helped her heave the body onto the back seat. He guessed it was a shot to the heart, no sign of blood, quick and clean. He took the gun, a .38 automatic, levered a round into the chamber and returned it to her. She dropped it in her handbag.

Ride with me, she said and he climbed in. The imprint of the man’s palm on her cheek was fading as she drove.

You don’t say much, she said as she steered quickly through traffic, but then you never did.

He nodded and, knowing he was safe, fell asleep. When he woke up, it was dusk and they were deep in the country.

I’m taking you home. Is that okay? He merely closed his eyes in agreement. How have you been, she asked.

She turned into the drive, a long one, to a house set well back. It showed no lights, and she was not bothered that he hadn’t answered.

We’ll bury him in the rose garden, she said. He loved roses and he’d like that. She pointed to the side of the house. There are gardening tools there.

Obediently, he went and found them. They took turns digging up the rose bed, the soil was soft and loamy. She took the dead man’s feet, he took the shoulders. They dropped him in the grave and shovelled the earth back. When they finished, he meticulously patted the earth flat and then helped her re-plant the roses. He couldn’t tell the colour in the darkness, but their smell reminded him of his homeland where roses blossomed to the size of a fist and caressed the air with their perfume.

Why did you marry him, he asked when they were sitting in her catalogue kitchen, gleaming with gadgetry, all wasteful in his eyes. His taste in food was austere and simple – leavened bread, spiced vegetable, pungent onions – enough to sustain him in the mountains. He noted, but said nothing, that she had used a key to open the front door while the kitchen one was unlocked. She poured herself chilled Chablis but didn’t offer him any as she knew he didn’t touch alcohol.

I fell in love, I suppose, why else does one marry?

She had a worn beauty, like a well-rubbed coin, still revealing the profile of a queen or a princess.

He was gentle in the beginning, she continued, then he became a beast, as all men do with the passing of time. He knew you were coming, and he knew I’d be waiting for you. I never stopped waiting for you, and he knew that too. He knew my password, it’s her name. When I typed it in, I thought of her and now when I do, I am reminded of her. You took your time.

I have time, he said.

So do they.

How did they kill our daughter? He waited until she refilled her glass, the wine sending a faint blush through her cheeks.

They had found her hanging from the clothes hook on the back of the door in her room, she said in a whisper. They said it was suicide, young people do that in their depression, and then they said it was a drug trip. My heart broke into small pieces when I saw my dead daughter and it will remain in lost pieces until the day I die. I didn’t know until then how frail the heart is, it broke like dropped china.