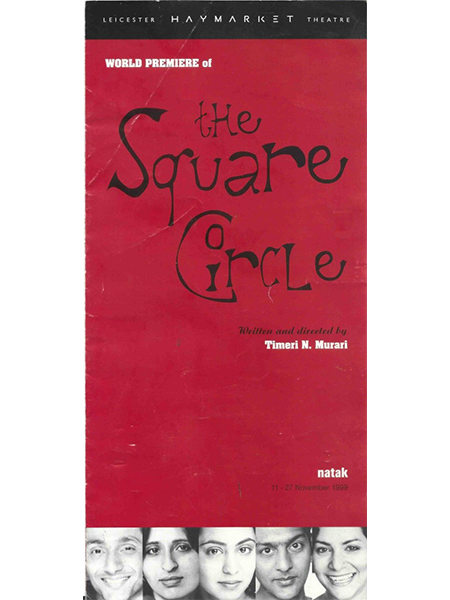

THE SQUARE CIRCLE 1999

(Leicester Haymarket Theatre)

Writer/Director

I adapted

my screenplay to the stage and directed it

Sita:

Parminder Nagra. Lakshman/Lakshmi: Rahul Bose. Vinny DhiLlon, Nitin Ganatra,

Harvey Verdi.

Producer:

Vayu Naidu. Sponsor: British Council, Chennai.

A swift and shocking rape is at the heart

of this play, written and directed at the Haymarket Studio by the author of the

original screenplay, Timeri N Murari. Sita, a young village girl kidnapped for

prostitution on her wedding eve, escapes only to be violated as she tries to

journey home. She is befriended by a travelling actor dressed as a woman, who

coaches her in dressing and behaving like a man to get her revenge.

Shakespearean

elements of cross-dressing and the exploration of sexual identity sit easily in

an Indian context where love has nothing to do with marriage and sex has little

to do with love. And despite the centrality of the rape, it is a funny and

tender play in parts.

Bollywood actor

Rahul Bose gives a wry, beautifully arch performance as Laksmi, the would-be

great artist, and Parminder Nagra movingly portrays the abject terror of a

child, the growing sensuality of a woman and the absurd posturing of a man.

Sometimes, as dusty day changes to ominous night, you could be watching a timeless Indian folk tale on Kamini Gupta’s spare and evocative set. But 20th century reality is ever-present in the revving of motorbikes and headlights of passing cars, and in the jeans-clad rapist (all the more chilling for the circling, silent hand-springs he performs before the assault).

The supporting cast of Vinny Dhillon, Nitin Ganatra and Harvey Virdi create a colourful microcosm of Indian society, further authenticated by Paul Jacob’s original score. The Square Circle; Theatre review Leicester.by Pat Ashworth for The Stage.

Timeri Murari’s tale of gender roles and preconceptions which won acclaim on the big screen is now making its world stage premiere at the Haymarket. It follows the story of Sita, an illiterate Indian villager, who is kidnapped on the eve of her marriage, escapes but is raped trying to find her way home. She is befriended by a transvestite who earns his living as a travelling entertainer and together they make the journey back to Sita’s home – he dressed as a woman, she as the man for her own safety. What is entertaining for British theatre is undoubtedly a challenging and controversial one for Indian culture, as cross-dressing men, a harsh questioning of gender roles within Indian society and the appalling treatment of woman as submissive objects are not subjects to be dealt with lightly.

Murari manages to create a pacy story which is full of humour and pathos without treating his issues irreverently.

Indian film star Rahul Bose excels as the cross-dressing Lakshmi/Lakshman, womanly without being effeminate yet always maintaining a hint of maleness, and Parminder Nagra’s Sita blossoms with increasing maturity as she struggles to encompass the masculinity she despises in her quest for revenge on her attacker and a way home. – Lizz Brain, LEICESTER MERCURY.

I wouldn’t call Leicester a city; it’s a county town with few pretensions. Except it must have more bars than shops. On Friday and Saturdays nights, Leicester’s white youth pack them to the rafters, competing to be drunk and bedded first. The girls are skimpily dressed Barbie dolls and the Barbie men are in their Gap uniforms – jeans, shirts hanging out, and ugly shoes. For a town with a sixty- percent Asian population, on those nights, there’s not a brown face visible among the sea of white kids.

Surprisingly, Leicester has a major theatre – The Haymarket, a 1970s red brick building perched on top of a shopping mall in the town centre. It is, along with Manchester, Birmingham and others, one of the Big Eight regional theatres. More surprisingly, the Haymarket had commissioned me to write and direct a play with an Indian setting for it’s Asian Theatre initiative, Natak. The play will be a rare original production for The Haymarket and it’s meant to draw the Asian population into the theatre’s fold. I’m not so optimistic; expat Indians are very conservative and the India they want are the masala films, not a controversial play about women. I now believe a play about Friday night drunks would be more socially relevant.

My producer, Vayu Naidu, the Artistic Associate of the Haymarket, is a tall elegant woman. Vayu is a force in herself – a wonderful storyteller, a playwright and an actress. We began with a grand tour. She flung open the doors of the main house – it was magnificent, a 725 seater with a huge proscenium stage which would be the perfect setting for my play. The doors closed with finality. It wasn’t my stage. The main house reserved for the Haymarket’s major productions; it’s huge musicals, which are their money-spinners. I went up another flight into the studio theatre. It was dark, tiny and the lighting rig pressed down like the brows of a Cro-Magnon. The 120 seats were raked and the first row was on the stage floor. My play, The Square Circle, was a road story set in the huge Indian landscape. This stage had more width than depth – diamond shaped with blunted edges- and I panicked at the thought of compressing my play and India into such a claustrophobic and eccentric space. All my stage directions would have to be re-written. I’d already had done one re-write when told that the Haymarket could afford only five actors for nine roles. Three of them would be doubling or tripling. Now I’d have to squeeze further. My play had over 20 locations and I would have to use lights, sound effects, and the audience’s imagination, to transport my players across the landscape.

I had wanted Nirmal Pandey, a fine actor, who’d played the male/female role in the film. But he wasn’t available. My brief was to cast that role in India. There wasn’t a vast choice of stage actors, apart from Nasrudeen Shah and Roshan Seth, both too old for the role. So, I sent the script to Rahul Bose, having seen him in a film, who was also known as a stage actor. He responded in 24 hours, accepting the role.

However, the most important role was the girl – she had to look around 17, play the male at times, evoke huge emotions and be physically agile. I had to cast her and the three others out of London. Where to find them? Spotlight, of course. Spotlight’s virtually the size of an encyclopaedia Britannica of actors and actresses. I spend days turning over the glossy photographs, looking for the few Indian faces. I culled out 25, male and female. Their agents sent me their photographs and their credits. All were impressively professional actors. I called them for an audition in June and it was held in a small room at the Drill Hall in London. I had staggered them 15 minutes apart but they turned up at the same time.

I was mainly looking for my Sita. I heard of a good actor, Parminder Nagra, and was relieved when she did show up for the audition. She was petite, quiet, hidden under layers of baggy clothes and looked right of Sita. She convinced me further by her acting a short scene. Auditions are brutal- in 10 to 15 minutes the actor must convince the director he or she is right for the role. It must be a depressing but necessary part of an actor’s life. It’s equally difficult for the director, sifting through the talented for the right one. The wrong choice can ruin the play. After a long day of seeing actors acting short scenes from the play, I was drained. But I had Parminder, Nitin Ganatra for the male roles and Vinny Dhillion for two female roles. I still needed another actress. Vayu suggested Harvey Virdi but as she couldn’t make the London audition, I arranged to do it in Leicester. She was good and having agreed my cast, their agents told me that none of them would commit to those dates – just yet. June to October was an aeon away and I’d have to wait until September to get their ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

I had to live with that but more important was my set designer. I had my ideas for the set – a hint of landscape to be more evoked than built. But how could I explain ‘India’ to an English designer more familiar with a gentle English landscape. The Haymarket suggested Kamini Gupta. Kamini was elusive. I had a dozen numbers for her and finally tracked her down to an answering machine in a Buddhist retreat in Devon. I left the message and waited. She called on the weekend as she’d taken a vow of silence! I saw problems with a silent, retreating designer. I trekked down to Devon on the train for a lunch meeting. A low key, gentle woman met me at the station in an antique-ish MG and took me to her retreat. We walked and talked and I told her what I imagined. Thankfully, she had worked in the Haymarket’s studio before and knew the space. And, as she was half-Indian and had lived in India, knew what I wanted evoked. We agreed to work together – through the Internet.

I spent the time in India doing a re-write to fit into the studio, blocked the moves, commissioning the music (Paul Jacob, a talented composer in Madras), recording the sound effects and buying costumes and props. This would save the Haymarket a lot of money compared to English costs. I was grateful that both The Hindu and the British Council in China came in with some financial support.

Kamini set up a web site for me to look at and we too’d and fro’d across seas and continents in seconds, through our computers, discussing changes, colours, moods of her drawings. I liked what she had done – a Banyan tree divided at the trunk with outspread branches and roots upstage, a blue sky and terracotta ‘earth’. It was simple yet effective enough to evoke an India and the tree was three dimensional instead of on a flat.

England in September was cool. We had our first production meeting on the 10th and I should’ve guessed we were in problems when the production manager, John Page, confessed there wasn’t a budget. We were a month away from rehearsals and no budget!! What about the set, lighting designer, marketing? Without a budget, the Haymarket hadn’t thought my play through. Also, Vayu, my link to the Haymarket, wasn’t present. She was rehearsing her own play, writing another, producing another. I was facing a table full of strangers. They were the in-house team – stage manager, painter, lighting, sound, set-builder, costumes. Kamini and I were the outsiders. She unveiled her model and gave her pitch. The Banyan would have to be built outside and as there wasn’t a budget, they couldn’t put down a possible figure. The costume department also didn’t have its budget. I discovered later that costume hadn’t even read the play.

The Studio was the poor cousin to the main house. All the resources, financial and technical, were at its command. They were opening Stephen Sondheim’s ‘Sunday in the Park with George’ and had no time for The Square Circle. And later, when ‘Sunday’ closed, they’d be gearing up for ‘Oliver’. I’d be lucky for any crumbs.

The one consolation was I had my Sita, Parminder. She had finally agreed. I had seen her in a play and she had enormous stage presence. We meet over a lunch and she admitted her role was intimidating, emotionally and physically. She would be on stage from start to end – dancing, kidnapped, raped, changed to a male, kills her rapist and is nearly killed by her own father. She told me after her first reading she just stared blankly at the wall for two hours worrying what she’d let herself in for.

The other male actor had to play three roles – father, kidnapper, rapist- apart from the father; the other two were unsympathetic. I wanted Nitin from the moment he’d walked into the audition but again I couldn’t get the commitment before we began rehearsals. I spent days auditioning and meeting other actors, none of them quite right. A week before rehearsal date, Nitin agreed.

By this time, having moved to Leicester and spending days in the Haymarket I began to meet others who fell like skeletons out of the closet. Kathleen Hamilton, a slim, pretty woman was the Executive Director, Kim the finance director, Paul Kerrystone the Artistic Director. My own crew was Farlie Goodwin, my ASM who’d keep the book, Karen on costumes and Andrea my stage manager. Through Kamini, I had found a very good lighting designer in Doug Khurt. Doug really liked the play and we huddled together discussing how we’d have to recreate roads, dhabbas, temples, forests, rivers, cars, motorbikes and houses through the magic of lighting, and my sound effects.

I had a three week rehearsal; schedule – never enough time- 10 to 6 5 days a week and a half day Saturday. The Haymarket’s rehearsal rooms were a 5-minute walk away in Short street. We had the top floor, full of skylights and huge windows. Fine during summers but in autumn with the sudden cold spells, we all nearly froze. In the main rehearsal hall downstairs, they were rehearsing the children for ‘Oliver’.

Rehearsals are a time of intense meditation, intense intimacy. The world was excluded, wars, famines, floods, elections were distant whispers from another world. From ten to six we lived together, ate together, talked of little else but the play. Working with such professional actors as Parminder, Nitin, Vinny and Harvey was a challenge, a learning experience and a delight. Why do this? How to say that? Why, who, what, where? Questions that constantly need answering, problems that need to be solved instantly and the right answers too. Part of the problem was also that none of them had ever been to India.

Actions that work on paper don’t work on stage, clever lines fall flat or the actor finds them difficult to say and had to be re-written. It’s a complex play of sexual identities, love, revenge, humour, seduction, and tragedy. It has to be played right, paced right. I have a fear of boring my audience, even as I have been often bored in the theatre.

As there are two violent scenes in the play – a rape and a revenge- I used a fight choreographer. Rennie is a tall, calm English actor specialising in theatre fights and he choreographs, step by step, in slow motion at first, a quite graphic and horrific rape scene. I have to admire Parminder; she does it but twice breaks down in tears after the emotional trauma of the make-believe rape. Nitin the rapist is also disturbed and upset by it. Thankfully, Parminder and Nitin are close, almost brother and sister, and she accepts his brutal mauling.

I get a budget finally, two weeks before opening night. There’s not enough for the full Banyan tree so Kamini has to lope off the branches and make do with hanging vines. Doug is having problems getting all our lights. Rahul is having problems with his Indian wig and costume can’t afford a new one. I’d like ‘blood’ for the revenge scene, but as that’s not in the budget either, Doug and I plan to use lighting effects to evoke that. Despite these minor setbacks, the experience of staging the play is exhilarating.

On Monday of the last week, rehearsal is ‘tech week’. The Banyan is moved onto the stage, the floor painted and Doug and I focus the lights. We begin our tech rehearsals with my actors and work for three gruelling days. We start at ten and finish at ten. Doug has fed a hundred lighting cues into the computer, along with my music and sound effects. A full dress with tech takes place Wednesday evening and another one on Thursday morning and again at two in the afternoon. In costumes, with all the effects and on the stage, the play comes to vibrant life. I couldn’t have asked for a better, hard working talented cast.

The play opened on Thursday November 11th at 7.45 in the evening. The audience is sparse but important – the Haymarket staff who’ve witnessed a hundred plays. I’m especially pleased when Kathleen and Paul say they love it -–and they’re not being polite.

Press night, five days after we open, is the night and we all dress up, the cast is excited. But it turns into a damp squib. Apart from the local press, the Haymarket can’t entice the national critics up to Leicester. The critics are notorious for never leaving London, if they can help it. All the regional theatres complain about their indifference. The Leicester Mercury does give the play a good review. But even without the review the box office, through word of mouth, is picking up. It rises to 60 a night and on the last two days we have full houses. As I expected, 85 per cent of my audience was English. The Leicester Asians weren’t about to embrace theatre.

The play closed on Saturday 27th November, the performances gone forever, as theatre is so ephemeral. It could be transferred but that exciting experience will never be the same again for me.