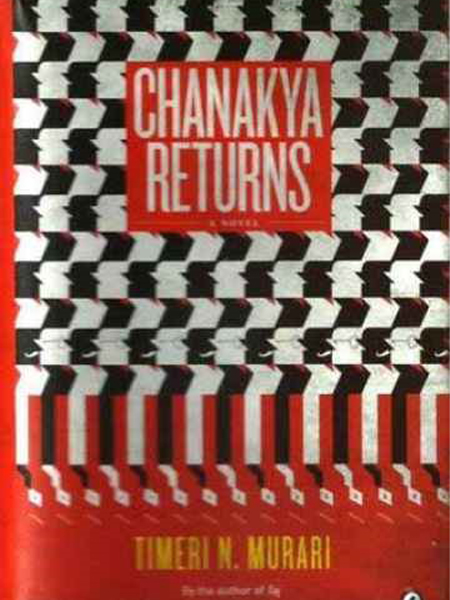

CHANAKYA RETURNS

Aleph 2014

History collides with news, emotion works with ambition, and imagination plays with reality in a thrilling read. Love and Power are both drugs and Chanakya Returns tries to keep us addicted. THE HINDU

An unputdownable political thriller from best-selling author Timeri Murari. Chanakya Returns covers a vast canvas of power, love, history, politics, betrayals, sex and more. It is narrated by Chanakya (370-282 BC), reincarnated in the contemporary world as the adviser to Avanti, the daughter of the head of a nameless state in India. THE TELEGRAPH.

Chanakya Returns is so apt a theme for our upside-down times that it is surprising no one had thought it up before Timeri Murari. TSJ GEORGE, New Indian Express.

The book in essence is an invigorating read. It does demand some attention and pondering, however that is only valid given the context. The writing is stark and precise. TIMES OF INDIA.

Chanakya, reincarnated, asks the reader to chose between the power of love or the lover of power.

And as the story grows, Chanakya slowly seeps into a powerful position of the top political family of the country, as the trusted and capable advisor to almost everyone in the family. From the beginning, the story anchors you with deep thoughts and beautiful description of power play, of love and betrayals. shadowdancingwithmind.blogspot.

Politically, the dynamics of this tale is fascinating. Murari presents Chanakya as a man who renounces all idealism in favour of naked ambition. Aditya Wig

History collides with news, emotion works with ambition, and imagination plays with reality in a thrilling read. Love and Power are both drugs and Chanakya Returns tries to keep us addicted. Love and Power are both drugs and Chanakya Returns tries to keep us addicted. Many have tried to resurrect the legendary maestro of political puppetry and failed. Timeri N. Murari, with his latest work of fiction, bucks that trend.

Chanakya’s overwhelming legend has intrigued many of us. Whether it is the picture woven by the Amar Chitra Katha, watching TV stories about him, or just reading his work and his life as adults, we wonder what it would be like to dig deep inside his head. To have him land up in our times, and express himself through his work certainly has our attention.

A modern day Chanakya rises through the ranks to help his ward Avanti negotiate the labyrinths of power and love. Characters and personalities pass by as the journey gathers speed and the bumps start increasing. And, like the Maurya scion in history, the dynast is handled with care; tough decisions being made on the way.

As a writer, this is stepping into a lesser known world where history collides with news, where emotion works with ambition, and imagination plays with reality. Comparisons with real life people and situations may exist — guessing who’s who, and drawing parallels with father-daughter relationships is tempting — but it takes away from the core story. The characters — what they are, and what they bring to the (reading) table — are strong, and the author knows them well. He has visualised them, explored their minds, hearts (and bodies) and opens them out for us — but only as much as Chanakya, the master craftsman, would have us know.

The paradox of power and love comes to the fore. The two try to coexist, cooperate, collide and cross over. And sometimes, the choice has to be made… The book makes its own choice. Power is its strength, and love is its weakness. Power and love are incompatible, Chanakya believes, and the book agrees. In Chanakya Returns, the corridors of power far outweigh and out-value the streets of love. The drama is in the power, and there lies the story. The thread of a route to power, about choices that one makes, and the beauty of their consequences inspires us enough to turn the page quickly — for Murari’s prose and dialogues and style are well suited to paint pictures of the pursuit of power.

In love, the clever use of words makes great reading and fodder for thought. However, the power of love is more than that — it has to be felt through the reading, it has to be as tangible as the love for power that is your constant companion through the book. And the power of love remains hidden in this book – you are desperate for it to come through, you want to weigh both on the same balance.

There are a few lines that would bring a smile to the readers’ lips — the plagiarising Machiavelli, for one. But those moments of brevity are the seasoning. The meat is in the intrigue, the gravitas, the skulduggery when doors are shut and most lights are off. The shadows. That’s where Chanakya works from, and that’s where the book goes to roost.

This is a book that you want to like. You want a fair battle between Power and Love — you want both to reveal themselves, bring on their armies, and spill blood on the pages. You want it to raise questions about the way today’s politics works and to question if the greater good is fair justification for the blood-spattered journey. And it does raise some philosophical and moral questions.

If you like politics, a touch of history, and wheel within wheels, read the book, for it will pique your interest. But even if you don’t like these themes, read the book anyway, for you will be supporting a writer who has pushed boundaries across time and words and power and love. THE HINDU

An unputdownable political thriller from best-selling author Timeri Murari. Chanakya Returns covers a vast canvas of power, love, history, politics, betrayals, sex and more. It is narrated by Chanakya (370-282 BC), reincarnated in the contemporary world as the adviser to Avanti, the daughter of the head of a nameless state in India. In the course of the novel, Chanakya poses an eternal question: What shapes our lives – The Power of Love or the Love of Power? His protégée, Avanti, has to choose between love and power. The choice Avanti makes has all sorts of implications not just for herself and her dysfunctional family, but for the people of the state her family has ruled for years. In his previous existence, the historical Chanakya was exiled from his homeland and took his revenge on the king who was the cause of his misfortune by defeating him in a war. He was then responsible for anointing Chandragupta as ruler of the Mauryan Empire and advising him on every aspect of statecraft. In the novel, Chanakya provides the same services to Avanti. He manoeuvres the awkward young daughter of a charismatic, powerful politician across the chessboard of power to becoming a brilliant successful politician and leader in her own right. THE TELEGRAPH.

A political thriller like none other! Avanti is the daughter of the leader of an unnamed state. She thinks highly of Chanakya – the political tutor and mentor of Chandragupta Maurya. And guess what? Chanakya is reborn in the present world and is there giving sound advice once again. This time though the decisions are harder, the ones between love and power, and what they hold for Avanti. She needs to choose quick as her would-be tutor needs answers.

The book in essence is an invigorating read. It does demand some attention and pondering, however that is only valid given the context. The writing is stark and precise. I would not classify this as a quick read. It will take some time to get through it. Having said that, it is extremely readable and will make you see Chanakya in the modern scenario and situations. Times of India.

Author Timeri N. Murari gives you an insider’s perspective on the political power plays between a father and his daughter through an extremely well written narrative filled with intense characters. Avanti is the typical kid of a rich and powerful father and a timid and contrite mother, who is accustomed to the life of worldly pleasures. She is drawn to her father’s enigma, a consequence of his power, wealth and conniving character, without realizing the darker secrets behind his enigma. Chanakya, a victim of Avanti’s dad’s antics, has long sought revenge and finds Avanti his perfect pawn for his intentions. Thus, begins a series of events embroiled in love, betrayals and politics that forms the plot.

The author amazes me. He carefully entwines the story around Chanakya’s calculative mind. The protagonist, Chanakya, is eloquently devious, instilling seeds of ideas and playing around with the minds of the others so subtly that it seems like their original idea. He is a patient man who has waited for his turn for a long time, carefully plotting his plans in the mean time. Avanti is not very likable, be it her immature, father-idolizing, spoilt-to-the-bone self or the grown woman who disappoints the readers expecting her to grow up to a bold, honest politician. Shakuntala, who tries hard to prevent her daughter from following her father’s footsteps and fails miserably, has been portrayed as the typical unhappy wife who cannot stop hoping for her husband’s dawn of realization on right and wrong. All other characters that make their short lived appearances add their own flavor to this story.

It did feel a little slow in the beginning but the plot picks up at its own pace. Certain scenes like the guy with the suitcase seem unnecessary, prolonging the narrative. The political scenario is a clear reflection of the current Indian politics. The tribal rebels, the mining that would erase thousands of acres of Forests and its inhabitants and people’s woes are a little close to one’s home and you get to see the perspectives of the various people involved. It truly makes you ache for a just ruler. Read this book not just for a fine story but also to gain your own perspective on today’s politics. GOOD READS

Any tale narrated by Chanakya—the teacher and philosopher widely identified as ‘Kautilya’ or ‘Vishnugupta’ who authored the Arthashastra— would be intriguing. More so when the narrator is a spirit that is reborn to this world after thousands of years in the void. Rebirth is the reason for Chanakya’s presence in Murari’s world, but as for the how of such a thing, Chanakya replies, ‘I cannot answer… despite my years of non-existence, as I did not find [God]… I am embarrassed by this to a certain degree. Especially as I was a Brahman once, a believer in Mahavir and am now an unbeliever’. There is a beauty to simplicity, but it is entirely possible to wield Occam’s razor too bluntly.

Timeri N Murari is known for his bestsellers The Taliban Cricket Club (2012) and The Taj (2007). In his latest novel, he is no less engaging, speaking to jaded modern India with acerbic wit. His Chanakya—once Mohanlal, the son of a modern day farmer who finds himself possessed by the spirit of the ancient strategist—is a dry, humourless man who believes in neither God nor love, driven only by desires honed by ‘sucking on star dust for more than two thousand years’. Burned at a young age in an accident, Mohanlal finds that ‘something mysterious was growing in my mind… Mohanlal was receding; Chanakya was growing more powerful, claiming my thoughts and my heart’. The grown up Mohanlal, now calling himself Chanakya, is a somewhat unsummoned guide who inexplicably is given charge of Avanti, the daughter of the President of a nameless state in India. Avanti is conflicted between her love for her father, her ambition and the passion she feels for a filmmaker she wants to marry. The novel begins with the latter conflict: in Chanakya’s own words, ‘His name is Aditya, a nobody, and love will only lead her to the role of a housewife, serving one man and not a nation’. But Murari explores a more risqué angle as well; there are suggestions of a less than platonic relationship between Avanti and her father.

Politically, the dynamics of this tale is fascinating. Murari presents Chanakya as a man who renounces all idealism in favour of naked ambition. As his protégé, Avanti swiftly follows suit, rising through the party ranks as she sheds her scruples one by one.

On the eve of Avanti’s first election campaign, for instance, there is not even a suggestion in their council of war that the election be fought on real issues, or with the aim of actually bettering the lot of ‘the people’. Instead, Chanakya blandly states, ‘We make a list of promises for the poor, trailing them as a fisherman the hook in the flowing waters’. This may be a true reflection of today’s politics, but it is rather odd to hear Chanakya—a historical contemporary of the Buddha, born in a time of deep philosophy and sound morality— speak as though his understanding of dharma and karma were at the same level as those of today’s leaders. The character speaks as one schooled in the Arthashastra, rather than as the one who wrote it; and while his infatuation with actress ‘Siggy Chopra’ may have been intended to humanise, it trivialises instead.

The novel’s strength lies in its caricature of reality: Avanti’s best friend Monika, the daughter of the wealthiest man in the state, ‘lives in a thirty-floor building… [that] towers over the city and peers down at the slums at its feet’; while the mercenary habits of today’s godmen mean that— ‘Even on the pathway to heaven you have to pay the toll before you start the journey’.

In terms of style, the book is both brisk and eventful. However, in a curious choice of grammatical flourish, the text does away with quotation marks entirely; forcing the reader to either slow down and pick apart sentences individually, or speed up and sacrifice complete understanding in the pursuit of narrative flavour.

Chanakya Returns is worth the jacket price, but if it has a weakness, it is this: were it not for the fact that the narrator grandly declares himself to be the Chanakya, one could quite plausibly have imagined him as Lalu instead.

(Aditya Wig is Chandragupta Maurya the author of the forthcoming fantasy novel King’s Fall, an alternative history of)