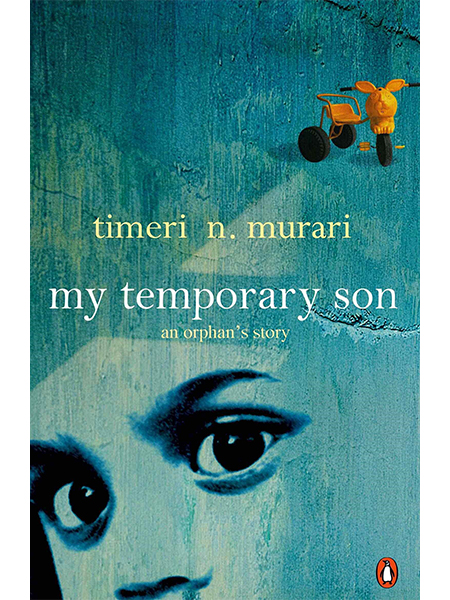

MY TEMPORARY SON

an orphan’s journey 2005

(Penguin India)

And two writers map different landscapes of loss and love with poignant and marvellously written memoirs: Joan Didion (Knopf) in The Year of Magical Thinking and Timeri Murari with his tale of losing an adopted child to another family in My Temporary Son. World Books. (Penguin India).

Truly a life-changing experience.

Experiences are so often described as “life changing” that the adjective seems clichéd, almost value less. But Timeri N. Murari’s book My Temporary Son is about a true life-changing experience – the story of a child bringing magic into two lives and teaching lessons of resilience and love.

It is a warm story of a little boy, an orphan with a fairly serious health problem, who takes over the lives of an elderly, childless couple who believe they have seen, done and experienced pretty much everything.

Tim and Maureen Murari are well settled into their respective routines; he a writer of fixed, rather reclusive habits, and she working with various charitable institutions and voluntary organisations. On a trip to an orphanage, Maureen chances upon one-year-old Bhima, a baby with impossibly large, expressive eyes, lying in an iron cot banging his head against the bars to distract himself from the pain in the raw, red mass of flesh on his lower body. And she decides, as she has with other destitute children before, to raise the funds for his operation and help place him with adoptive parents abroad.

For the first few months, Tim is just an observer of sorts, listening and providing emotional support to Maureen as she gets into endless rounds of consultations and tests with doctors and raises funds to correct Bhima’s vesical exstrophy, a condition in which the bladder is outside the body.

Maureen brings Bhima home “for a few days” after surgery; to recuperate till he is strong enough to resist the infections he could catch in the orphanage. The few days turn into 11 months as the Murari’s wait for Bhima’s adoptive parents from Europe to plough through the paperwork demanded by the Indian adoption system.

And during that time, Bhima transforms Tim’s life, drawing him out, teaching him to be a father. Tim and Maureen do as much for Bhima – sitting through the night to comfort him when he experiences night terrors, being attuned to his every mood, being there for him – as he does for them.

Though his early development was delayed because of his medical condition, Bhima proves to be an exceptionally intelligent and resilient child, capturing Tim’s and Maureen’s heart with his simple faith, intense curiosity, mischievous ways and his tremendous spirit for survival.

Tim also uses the book to provide insights into Indian society; he brings up ideas of karma and destiny, and the traditions, superstitions and beliefs that are so much part of Indian life.

Child labour, exploitation and discrimination, bureaucracy, the education system, the almost-hopelessly convoluted adoption process…simple statements, made almost in passing, reveal social attitudes to all these and more.

Finally, the mammoth Indian bureaucracy begins to move and Tim and Maureen find themselves facing the idea of life without Bhima. There is heartbreak but they have to confront the reality of their age, Bhima’s future and what is best for him.

A story like this – with so much of the writer in it – could easily slip into the mawkish and the maudlin but Tim maintains dignity in his prose while infusing it with a certain enchantment that comes from his clear and beautiful language.

It is also without explicitly being so, a story of many in India and around the world who find it in themselves to open up their lives and hearts to abandoned children and are willing to move systems across continents in their willingness to love. THE HINDU.

Timeri Murari tells a sensitive, moving story in prose that is spare and devoid of gimmick- and that is the book’s triumph. The emotion is powerful for being understated, the confusion of a 60-year-old faced with feelings he never thought he had is touching for being genuine. Lesser writers might have made a hash of this experience, the temptation to overwrite is strong. Murari’s style is at once concise and poignant.

The story is simple enough. An abandoned child, later named Bhima, is taken from an orphanage for a rare surgery for which Murari’s wife Maureen raises the funds. The surgery is successful, but rather than send the boy back to the orphanage. The Murari’s decide to let him recoup in their Chennai home. Bhima is not the first ‘house guest’ (as Murari refers to him initially). But he is special for some reason, and the manner in which the little one shines a torch on Timeri’s soul and light up emotions hiding there is the essence of the book. “He is your temporary son,” says one of their friends and it is then’ hat Timeri’s unspoken wish is first articulated.

Even for Maureen who is in touch with deep emotions within herself the change brought about by Bhima is startling. ‘Parenthood’ for the year that Bhima is with them brings with it all the doubts and certainties that first-time parents less than half their age live with. The Muraris cannot adopt Bhima because of the age difference (the law states that the parents cannot be more than 45 years older than the child).

The story is as much Bhima’s as it is the author’s. Both while showering the child with

love as well as when holding back in the cause of a greater love, the Muraris show themselves to be a rare mix of the romantic and the practical. They know that Bhima will soon have to leave, and that his adoptive parents from Europe are only waiting for the paper work to be cleared. So right from the start, Bhima is trained to call the Muraris ‘aunty’ and ‘uncle’ so there is no confusion with the ‘papa’ and ‘mamma’ to come. Love is as much about giving as about holding back. Closure is important, but it is not easy.

Certainly not after the kind of impact the child makes on their lives. As Murari writes, “I hate being interrupted while I am working. I try never to answer the phone and I ignore the doorbell. At one time I would have snapped and snarled at anybody who disturbed me. Now Bhima was teaching me things that work, no matter how important cannot take precedence over a child’s demands and needs. I was acquiring a new skill – that of being a. father. I was not used to it, to constant repetition and to just as constantly admiring him as he practiced new skills time and again and again. But I realized that every moment I spent with Bhima is what Americans called ‘quality time’ his confidence grew as he pushed at the boundaries of love surrounding him.”

We speak often about the loss of innocence that comes with age. Children help us reconnect with our lost selves. But here was a successful writer regaining innocence. The thought that such a thing is possible is charming in itself; the idea that age is no bar

There are too lovely vignettes of Chennai, of the memories that Timeri has carried with him of his own childhood: of the work done by Maureen and others like her who do good by stealth. But it is the sheer intensity of ultimately hopeless unconditional love that keeps a simple story from flagging or moving into areas that are of no relevance

Murari has long talks with his temporary son, explaining everything around him,

It does not matter that the child does not understand; the exercise is new to the temporary father, and he begins to understand himself and his childhood better is doubly comforting.

“In this long belated ‘fatherhood’,” writes Murari, “I wanted Bhima to experience

everything I had as a child growing up in Madras, in this house. I wanted to recreate

my childhood through him, as all fathers do, I assumed. It was important for him to remember something more about India, than the four walls of the orphanage that had contained him for so long.”

The irony is that while the ‘father’ was doing everything in his power to erase from the child’s mind the bad memories and replace them with good ones and thus prepare him for a life beyond the orphanage and Chennai, he himself was finding it increasingly difficult to distance himself from the ‘son’ although he knew that would be necessary. In the end all ironies and contradictions dissolve in the ocean of love. Timeri Murari has written about a dozen – works of fiction including the recently reissued Taj, about half a dozen plays and a couple of films. His writings have been marked by a detachment and attention to detail that only the finest practitioners of the craft can bring to their work. In taking the road from a professional detachment to an increasingly inevitable attachment he brings to the surface in this book an aspect of autobiographical writing that is both personal and universal

At the end of it, the author who has lived most of his life abroad is told that this is India and that with some sensible bribery could have adopted Bhima ‘legally’. The reader is left to wonder what might have been…SAHARA TIME.

Anyone with a child in their life, anyone who has ever longed for a child and anyone, but anyone, who has ever been at the receiving end of a child’s love will find something in this book. For even the most cynical will not be moved by Timeri Murari’s true account of caring for an orphaned and disabled child. Murari’s life took on a new meaning when baby Bhima entered his life. At first it was a nameless pair of deeply troubled eyes, a two-dimensional image from a photograph that was taken in the orphanage to which his parents, also nameless, had surrendered the child. A child who left a profound impression in the precious 11 months during which Murari became his father

My Temporary Son is a thoroughly honest, self-scrutinizing and, in places, brutal narrative. It documents young Bhima’s entrance into a hard world, and the inordinate medical procedures he undergoes, all the while following the author’s growing emotional attachment to his ‘son’.

Murari’s great skill lies in the way he encapsulates his love for baby Bhima, not by wild, gut-wrenching emotive adjectives, but by a pensive and almost introspective examination of his emotions, creating an altogether different but equally painful type of tragedy.

The author does not paint himself or his country as perfect. Indeed, it illustrates the wretched bureaucracy that that forms the basis of the adoptive process in India as both a curse and a blessing. The circumstances which led Bhima into the arms of Murari and his wife were far from easy and the author provided no palliative in his portrayal of events.

Murari and his wife provide a firm presence as the baby Bhima suffers and triumphs; there is pain in his surgery, his recovery, his first smile. His joy in discovering rain. This is a tremendously powerful book, and tragic, too, in its way. INDIAN EXPRESS