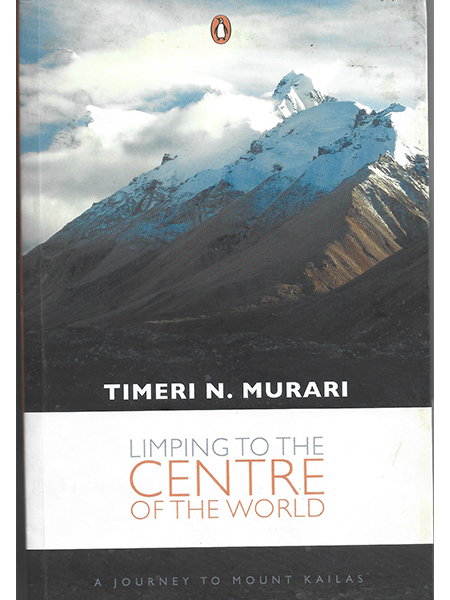

LIMPING TO CENTRE OF THE WORLD

A journey to Mount Kailash.

Penguin 2008

Limping to the Centre of the World is an awe-inspiring book which directly challenges readers to examine the foundations of their own spiritual beliefs and encourages them to consider those less fortunate in the oft uncaring world of today. All in all, Limping to the Centre of the World is a highly recommended read. DAWN.

There are various kinds of books. Some an eminently forgettable. Others can be read once. Murari’s latest is one to which one can go back at any time and read all over again, any number of times. NEW SUNDAY EXPRESS.

An increasingly personal, deeply touching, well-written book… I would say that after a long time I felt sorry to have come to the end of a book. THE HINDU.

I have never been more seized of the idea of making this trip after relishing Murari’s brilliant narrative. TIMES OF INDIA.

The deceptive lightness of the text is weighed down by philosophical profundity when Murari neatly juxtaposes scientific thought with Indian puranas to touch base with spirituality, and at the same time provoke uncomfortable questions on our tendency to endow God with human qualities. HARMONY

This is a dispassionate account of the incredibly arduous journey. It’s a lively read, engrossing in places, and an ideal guide for those planning to undertake the pilgrimage. INDIA TODAY

A Spiritual Pretzel

Trekking to Mount Kailas in a remote region of Tibet is not an endurance test for the faint-hearted, and throughout this arduous expedition Timeri N. Murari met each and every obstacle with a deep-rooted spiritual resolve which surprised even him.

Mount Kailas, located on the western Tibetan plateau, is held in extremely high religious esteem by those of Hindu, Jain, Buddhist and Bon persuasion — the latter being the sacred belief system of Tibetans prior to the arrival of Buddhism and an ancient religion to which a number of Tibetans still adhere.

Hindus consider this revered mountain to be the home of Lord Shiva and a pilgrimage to the site is considered highly meritorious. When Murari, a very skeptic Hindu, was notified that his name had been drawn from an Indian government computer lottery which offered him the chance of participating in a trek to Mount Kailas as a member of the ‘Kailash Manasarovar Yatra’ in 2005, he didn’t exactly jump at the chance.

Never having gone on a trek of any kind, given the prospect of an extremely difficult hike of over 200 kilometers in the most hazardous terrain on earth, at high altitudes and with late autumn and the possibility of bitter cold and snow on the horizon, the author – in his early 60s at the time and hampered by a severe knee problem which has periodically aggravated him since childhood — could have been forgiven for chickening out.

However, a child whom he and his wife had fostered, until he was found a permanent home in Europe, was due to undergo major surgery and it was in the form of a hopeful prayer for the surgery’s success that Murari finally decided to pick up this rather timely gauntlet.

Recently published by Penguin India, Limping to the Centre of the World is the surprisingly blunt story of Murari’s physical and spiritual journey into, what was for him, the complete unknown. He utilises some extraordinarily beautiful phraseology combined with sharp-edged witticism to take the reader along with him on the epic adventure.

No stranger to the literary world (Murari is well known for his bestselling novel Taj: A story of Mughal India and other publications, plays and films), the author has a wry way with words, using himself as a metaphor, that often borders on the droll.

On finding himself precariously balanced on a dangerous ledge high above the River Kali at the outset of his trek he observes, ‘the ledge isn’t a trek but an assault course, and the men who hewed it didn’t even have the decency to pave the pathway evenly but just dropped rocks and stones wherever they fell, no doubt exhausted by their labours.’ Having to hold tightly onto the hand of his porter for balance he writes: ‘This hand-holding does not embarrass me: all of us, at some time, need a young man’s strong support.’

The going is tough and in no time at all, despite wearing a specially-designed brace on his right knee, his left leg is also giving problems. ‘As the knee bone is connected to the ankle bone, to paraphrase an old song, my left ankle has weakened and it, too, is strapped. The human body is a perfectly engineered piece of work and we’re well balanced bipedal creatures who can surmount any terrestrial terrain, but I stand like a twisted pretzel as I’m putting all the burden on my right leg.’

Murari introduces readers to his interesting, somewhat unlikely yet perfectly plausible travelling companions all of whom, except for one, are equally thrilled to have been selected to undertake this privileged pilgrimage. All these people are, in their very ordinariness, fascinating in their own ways.

Pettiness, a customs officer with a penchant for designer skiwear, nightclubs, ladies-of-the-night in the most unexpected location, food and accommodation which left much to the imagination, recalcitrant yaks and their keepers are all packed tightly in between the pages of this highly entertaining travelogue. As are a suspiciously romantic scandal, a Tibetan monk straight out of The Last Samurai and stranger than fiction characters such as the Russian Orthodox priest with his female companions in tow. The weather, which was mostly harsh, wet and freezing cold, has its own role to play in this thrilling saga as do the very stones, boulders and mountains along the trek.

Limping to the Centre of the World is an awe-inspiring book which directly challenges readers to examine the foundations of their own spiritual beliefs and encourages them to consider those less fortunate in the oft uncaring world of today. It is also, in some ways, a tribute to the love of one human being for another, in this case that of Murari for Bhima, his short term foster child, whose full story is told in another of this prolific author’s books, My Temporary Son: An orphan’s journey.

All in all, Limping to the Centre of the World by Timeri N. Murari is a highly recommended read. DAWN (Karachi)

Magic Mountain.

I have always wondered what it would be I like to make the journey to Mount Kailas, considered to be among the holiest of places by the Hindus. As a child I remember reading with fascination an account by Subramaniam Swami published in the Illustrated Weekly of India. He was in the first batch of pilgrims who were allowed by the Chinese to undertake the arduous trek. Since then, the fascination with Kailas has only grown. As I step closer to middle age, the uncertainty of whether I will ever be able to make it has also increased.

Timeri N Murari (Tim) is a man who has written on a wide variety of subjects. Among his most poignant works are Four Steps from Paradise and My Temporary Son — An Orphan’s Journey. While the first is a work of fiction into which many have read shades of an autobiography, the second deals with the growing attachment the author and his wife develop for an orphan infant who spends a few days at their household before his eventual adoption, The child Bhima is one with whom I have laughed and cried as I read the book.

Bhima is to undergo a surgery in his distant home in Europe and Murari, desperately wanting the child to successfully come through, somehow draws his strength from Mt Kailas. He applies for the yatra that is conducted by the Government of India, only to have second thoughts when one of his knees gives way. However, the mandarins in Delhi or wherever move in a mysterious way their wonders to perform (or was it Kailash?) and include his name among the yatris despite his informing them of his inability to join. So he does go ahead.

What follows is a delightful read. In some ways it is like reading Corbett. There is the same attention to detail, the ability to lead the reader on a visual treat. Each rocky ledge, each landslide and foaming river is described as the eye saw it. The text has a certain fluidity that the trek in reality did not, for Murari’s route was arduous, the knee not helping matters.

The humour is abundant and reminds me of Dervla Murphy, the woman traveller who wrote so many wonderful accounts of her trips to various parts of the world in the 1950s and ‘60s. Making it lively and full of perhaps unintended humour are Murari’s co-yatris. There are ardent bhajan singing (and dancing) devotees fiercely religious men who don’t hesitate to use their official clout when necessary to bend rules in the name of piety, young men who see it all as a trek, women who are searching for Shangri-La and a couple who bring a whiff of scandal — Is he married to her? Apparently not. They are under different names and yet together. Then you have superior government doctors, bungling bureaucrats, statistics-spouting foreigners and recalcitrant porters and submissive mules. It is a microcosm of what any trip in India entails, only that this is to a place that most of us can only aspire to go to.

Murari makes it to Kailas and his description of his reactions and those of his fellow travellers on seeing the mountain is one of the best passages in the book. It is an emotional high, a sense of achievement and one of a cry for succour. The author starts off on the trip as an agnostic, becomes silently communicative with the mountain and returns in perfect peace with himself. Yes. Bhima survives. Was it because of Kailas? That is an inference the reader has to draw.

There are various kinds of books. Some an eminently forgettable. Others can be read once. Murari’s latest is one to which one can go back at any time and read all over again, any number of times. NEW SUNDAY EXPRESS

The Lost Horizon.

Towards the end of ‘Limping to the Centre of the World’, the author writes the crux of the book: “I want to be in harmony with the plain. the mountains, Kailas, the wind.” Murari’s “centre of the world” is Kailas; the book is a memoir of his pilgrimage.

The author-hero of this voyage, a 64-year-old man with a damaged knee, embarks on a trekking expedition to Tibet with a large group of pilgrims. Cynically removed from his bhajan-chanting fellowship, he has one spiritual quest though: to pray for the well-being of his godson Bhima. Taking parikaramas around Mount Kailas and Lake Mansarovar mark the fulfilment of his mission.

Spiritual journey

The journey begins in Delhi from where the group bus to Dharchula, a border town and thence to Mangti and Gunji. From Dharchula, the yatra begins on foot to Lipu Lekh Pass which is almost 600 metres higher than Mont Blanc in the Alps. The stoic but dangerous river Kali accompanies this motley group of yatris, ponies and ghorawallahs and is among nature’s first symbols that put human potency to the test. “The survival of the fittest” is imbibed instinctively as the author humorously recounts how the healthier among them are able to move faster and occupy better rooms and beds. The journey culminating in Mount Kailas has other sermons in wait for the agnostic traveller. The sublime mountain effortlessly diminishes the human will that dares to conquer it.

Many of the writer’s closely held beliefs can be discovered in the book. When he consumes his confectionary he puts the litter in his pocket. There are portions of the book where he shows his acute sensitivity towards the degradation of nature by humankind. His eco-consciousness is carried afloat in a physicist’s mind when he warns against the rapid melting of the Himalayan glaciers or the shrinking of the tiger population in our forests. Although this marvellous book soars away from everyday reality, the author’s political views about colonialism in India and Tibet as I well as his premonition about the Maoists overthrowing the monarchy in Nepal come through in a well nuanced way

In so many ways, this book is reminiscent of Atwood’s Surfacing. Both authors attempt to reclaim nature from the “unsettling and turbulent world below the mountains”. As Murari writes: “I want to stop, to open my arms, to enfold the hills, the mountains, the rivers as long-lost brothers, sisters, parents that I lost touch with”. He may ostensibly he making the journey for Bhima or even to put his body to the ultimate test, but he finds him self slipping into a kind of asceticism, willing the reader to join him.

Metamorphosis

Murari’s slow metamorphosis is evinced towards the end when he chants ‘Om Shivaya namah” invoking Lord Shiva’s blessings. He has moved a long way away from believing that the gods are hard of hearing: “I do feel … that I am near something spiritual that is touching me very deeply. I am also touching the belief of all those who have come here before me over the millennia, giving it its sacredness, for without them this would be merely another mountain.” And so, Murari gets more than he bargains for. He has little notion of the hardships of the climb and hasn’t sufficient warm clothing either. But despite all the obstacles, his mind is unwavering and determined as he makes it to Takalakot, the first Tibetan occupied town on the other side of the border. When finally he comes face to face with Kailas after crossing the excruciating Dolma La pass, he weeps as he breaks his own physical and mental barriers.

It suffers from having a rather unimaginative title. Unfortunately, its subtle humour also declines as the experiences become more spiritual (and less sensational) towards the last third of the hook. Notwithstanding, I would say that after a long time I felt sorry to have come to the end of a book. THE HINDU

A TRYST WITH SPIRITUALITY

After reading Timeri N Murari’s account of his expedition to Mount Kailas and Mansarovar one is left with a heartfelt longing to walk the same road one day.

But for a series of coincidences, this journey might never have been. The journey to Mount Kailas, the abode of Shiva, is a treacherous one through inhospitable terrains where facilities we take for granted are luxuries hard to come by. It’s a journey that only the believer or the brave heart can endure. And Murari is a bit of both.

Though the computer randomly selected Murari’s name from amongst thousands of applicants, the author promptly sent in his regret on account of his ‘badly damaged knee.’ Obviously someone in the Kailash Mansarovar Nigam Limited forgot to take note of this. Because this is a journey pre-ordained and divined. “You have very high BP,” the ITBP doctor pronounces after examining Murari. Again, when God proposes, man can only do so much. Murari climbs every mountain.

The journey is a leap of faith for the author, a self-avowed critic of organised religion. He’d struck a deal that while he would make this trek to this supremely sacred destination, in return, Kailash would watch over his ‘temporary son’ Bhima when he would go in for surgery in a few months time.

His prose is delectable and when he describes a place, an incident, or even thoughts that flit in and out on encountering nature in all its bare glory, Murari draws a picture that the mind can see so vividly. When he talks of the mule Lali falling into the vicious Kali, the reader is very much part of the excitement and suspense. Similarly,

when he talks about the different characters that comprise his batch of yatris, each one takes on a face and persona in the reader’s mindscape. So even by the time you are half way through the book, you know the people. The garrulous Pandey, a police official, who manages to get himself hot water when everyone else has to go through biting cold water baths; the reclusive doctor and his friend who keep to themselves; the devout men and women who break into bhajans every so often. Then there is the officious Lamba, whose whistle-blowing drill irritates the author as much as his refrain ‘comfortable, Mr. Murari?’ grates on his nerves.

But the best imagery is reserved for nature. Sample this: The snow flurries have stopped and Kailas is etched against an achingly blue sky. It looks serene and magical and inspires many prayers…

My city-bred bones are cushioned in comfort and much too steeped in a secure way of life. Yet, I have never been more seized of the idea of making this trip after relishing Murari’s brilliant narrative. As for the author, having conquered the mountains and being humbled by it, he is a changed man. TIMES OF INDIA.

The Magic Mountain

Faith can move mountains but in this case it’s the other way around. Timeri N. Murari is a journalist—turned— author—screenwriter-playwright. His last publication was My Temporary Son, a factual account of Bhima, an orphan with a life—threatening deformity, abandoned by his parents. Murari’s wife raises money for an operation and the child enters their home and their hearts. He is adopted by a European couple, who take him for surgery, a high—risk procedure. Murari spots an advertisement for the pilgrimage to Mount Kailas, the ultimate spiritual experience for Hindus. Mount Kailas, the crystal mountain, is located in a remote part of Tibet under Chinese control. Hindus, Buddhists and Jams consider it the Centre of the Universe. The mystical mount has attracted thousands of pilgrims in search of miracles or nirvana, the definitive spiritual quest.

It is a quest not for the faint-hearted. Many pilgrims, including danseuse Protima Bedi have lost their lives on the yatra. It involves a 200—km trek over gruelling terrain in freezing cold and snow5 before one can circle the mountain. Murari is an unlikely pilgrim, an agnostic with a distrust of organised religion. He also has a dodgy knee and never trekked in his life. The hope that the pilgrimage will give him a chance to pray for the success of Bhima’s operation moves him to the mountain. This is his account of the pilgrimage and the epiphany he experiences. Others have written on the pilgrimage to Mount Kailas, but they were historians, adventurers or true believers. This is a dispassionate account of the incredibly arduous journey, the pilgrims who form a microcosm of Indian society (“never happy unless this are complaining about something”), the complexities of the journey, including the harsh reality of Tibet, and finally the moment when the magic mountain appears out of the mist and the trance-like awe and spiritual ecstasy induced in the parikarama. It’s a lively read, engrossing in places, and an ideal guide for those planning to undertake the pilgrimage. Murari’s transformation from sceptic to part-believer, and how the cathartic experience changes him as a person, is worth reading. Above all, it offers a valuable insight into why a remote mountain in another country continues to inspire thousands of Indians to undertake the toughest pilgrimage on earth. INDIA TODAY

Man versus Mountain

Six weeks after going through knee surgery, 64 year-old Timeri Murari trekked to Mount Kailas and Mansarovar in the Himalaya wearing a knee brace. Limping to the Centre of the World, however, is more than a diary of Murari’s arduous expedition. It’s also an engaging, informative and— at times—irreverent take on human nature, religion, spirituality and Indian mythology.

The author embarked on the expedition three years ago to invoke the almighty to save the life of a two year-old deformed child passing through his life. Though his desperation is at odds with his agnostic scepticism, Murari is not afraid to admit to the dichotomy. The same candour burns bright when he describes his fellow travellers who inject humour— with their quirks and whims—to what would have otherwise been a solemn pilgrimage. As you heave up the Himalaya with the author, you despair over the environmental degradation creeping into supposedly pristine terrain. The deceptive lightness of the text is weighed down by philosophical profundity when Murari neatly juxtaposes scientific thought with Indian puranas to touch base with spirituality, and at the same time provoke uncomfortable questions on our tendency to endow God with human qualities. Though the book ambles at a down-to-earth pace, the passages describing the might of Mount Kailas transport us to a higher realm. By the end, we wonder whether nature isn’t god after all. HARMONY