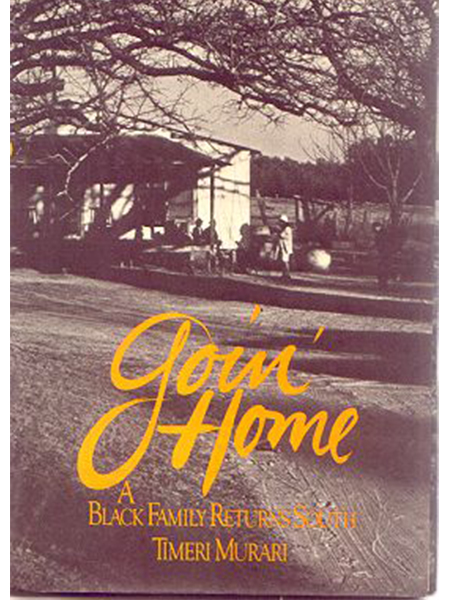

GOIN' HOME

A Black Family returns South. 1980

PUBLISHED: G.P. Putnams, New York. Also wrote the film documentary on the family for Thames TV.

‘Murari tells of their journey with sensitivity and candour, with sympathy restrained by objectivity His own point of view is that of an outsider – an urbane writer (novelist and playwright) who shuttles between London and New York. Murari conveys a complex reaction to Arthur, Alma and the South he visits. While he recognises pretence and hypocrisy in southern societies he is at pains to portray the civic leaders he encounters not as ogres but as basically decent – albeit extremely provincial – unquestioningly preserving a social milieu they’ve inherited from their ancestors. He is enormously sympathetic to the southern black’. THE WASHINGTON POST.

-This sparely written account of the Stanfords is a poignant account. A story of a 5th or 6th generation American family – land where my fathers died – who can’t find a home. A story of a myth – among those are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness- that isn’t working. A lament from sea to sea. THE BOSTON GLOBE

-In this family portrait that spans three generations, Murari sensitively explores the racial undercurrents that ultimately lead to this young couple’s painful disillusionment.

CINCINNATI HERALD

-The warm, moving, ultimately grim story of one young family’s participation in a growing movement: the black migration back to the South. Murari draws a telling picture of another black dream deferred. LIBRARY JOURNAL.

-‘Goin’ Home tells of a dream gone sour. It’s the touching story of Arthur and Alma, a young black couple. For some months, Timeri Murari had been searching for a black family planning to return to the South. He went along with Arthur and Alma and this book is their story, recorded with perception, sensitivity and sadness by Murari. BIRMIGHAM NEWS.

Timeri Murari has come up with a highly readable, bittersweet little book that is hard to put down once begun. The author, perhaps because of his own background, writes with a sort of low-key detachment that makes for absorbing reading. He also writes with rare perception as he compares the racial climates in the urban North and rural South. SUNDAY ADVOCATE.

The book is written with great understanding of the desire of Arthur and Alma to make it in Arthur’s hometown. The book shows that the left-out feeling that submerged them in Eufaula was more humiliating and degrading that battling it out with some admitted rednecks in Boston. St Paul Pioneer Press.

MILWAUKEE JOURNAL interview by Joy Lewis.

To the outsider, the South appears to be making good progress against racial barriers;

(more jobs) are pluses. school integration and industrial growth But, “racism has become simply more subtle– today, blacks can sit at a lunch counter but they’ve no money to buy

food,” Timeri Murari said, reflecting on economic realities for many blacks in the south.

“Goin’ Home” is the story of a black family, Arthur and Alma Stanford and their young son, who attempt to resettle in Eufaula, Ala., Arthur’s hometown. After seven years in Boston, the Stanfords packed their belongings in the fall of 1978 for greener and homier pastures. They planned to build a ranch house on -l0 acres belonging to Arthur’s father and grow their own vegetables. Alma intended to go to business school and Arthur counted on a decent paying job, paying not the $7 an hour he got in Boston spray-painting cars, but enough to support their dreams.

Murari, a 38-year-old novelist and playwright with apartments in London and New York, accompanied the Stanfords South. He is disarming, with a distinctly educated British accent. he too is dark-skinned and knows prejudice. Born in India,

“In early 1978, I read a newspaper account about how blacks were returning to the south from the industrial north. In fact, black migration north had nearly stopped,” he told me. “It was quite a phenomenon. I had never been south, and I was curious.”

“I think it’s better in the south,’ Arthur tells Murari in the book before leaving Boston. “There you don’t make as much but it don’t cost you as much to live and you can live more comfortable.

Murari spent several weeks in the bosom of the Stanford clan, chatting with Odie and Bud, Arthur’s parents, tagging along when Arthur tries in vain to get a bank loan (which had been promised before he left Boston) , going job hunting with Arthur, talking to Alma and other relatives, meeting civic leaders, and absorbing Eufaula’s present and past.

“A beautiful little town…like taking a journey back into the Confederate past,” he writes in “Goin’ Home.” “Everything here looks as if a deliberate attempt has been made to still time and bottle it.”

Sadly, the only job Arthur finds is at $2.65 an hour. The bank won’t loan him money unless his wife also works–dashing her hopes for business schooling. The longer Arthur and Alma stay, the more they grasp that their South and Eufaula have changed little. They learn that a dual wage system still operates–whites preferred over blacks, with more pay for the same work.

Disheartened, the Stanfords realize they can’t make it. In January 1979, they go back to Boston–defeated, they know, by racism they cannot disrupt nor escape. “I don’t think we was prepared for what stood in our paths,” Arthur says.

What frustrates the Stanfords almost as much as under-the-counter discrimination is the attitude of blacks who never left– Eufaula.

“I’ve talked to blacks Who live here,” Alma confesses in the book. “And when you talk to them and tell them how far they’re set back and that things need to change, they just look at you as if you’re crazy. They say ‘You can’t change it, we’ve been like this all our lives. “‘

“You know what I found out talkin’ to the black guys at work” Arthur asks Murari. “They don’t want nothin’. They’re happy just workin’ one day to the next. The South really hasn’t changed much you know.”

“Goin’ Home” is succinct. It shows Murari’s skills as a reporter in London for The Guardian. His descriptive passages are detailed but not overburdened. Thus, the story of a realistic dream moves quickly to an inevitable fate, given the social milieu of the south. Reading the story of an ordinary black family–in their own words– and listening to white civic leaders describe and assess the “facts of life” for southern blacks and whites is an eye-opener for those who Know little about southern living.

Historical accounts of the land Murari visits and the people he meets give the story fullness. Occasionally he digresses into his own terse philosophy. For instance, upon entering a down south savings and loan bank he comments: “Banks have no poetry, no prose, no songs, no dance. They always remind me of operating rooms–clean, sterile, well lit, and they bare the financial intestines of their customers. A digit here, a zero there, cleanly incised by the razor- sharp computers and adding machines. Only white people are to be seen behind the counters and in the offices.”

Murari keeps in touch with Eufaula and with Arthur and Alma who now live in Salem, New Hampshire. Alma recently finished business school and is a secretary; Arthur has an $8 an hour job in Boston. But, Arthur states in the book, he still desires to return to ~is roots: “One day, I’m goin’ back, goin’ home, for good.”